Insights

Part I: From scenic to semantic

Designing in the age of intelligence

By

Doug Cook

—

18

Jun

2025

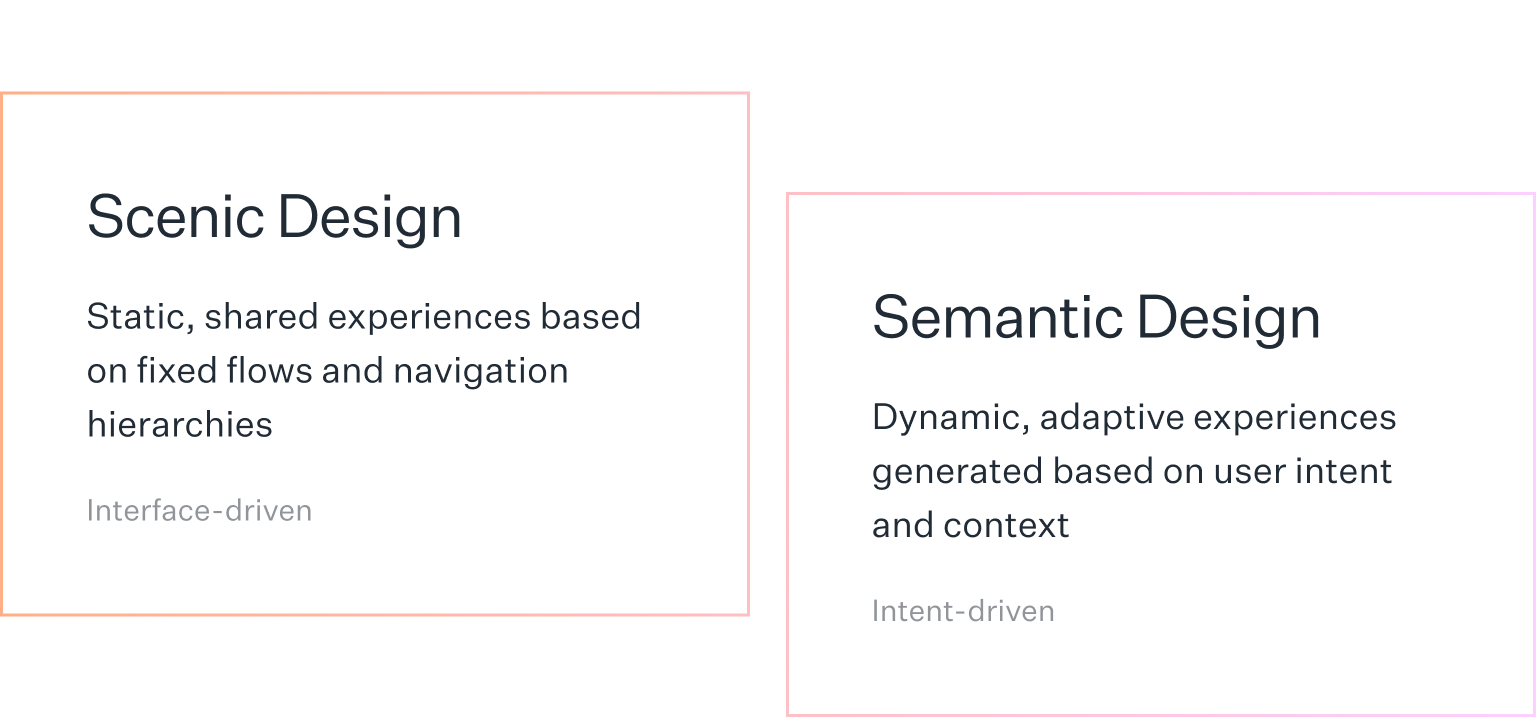

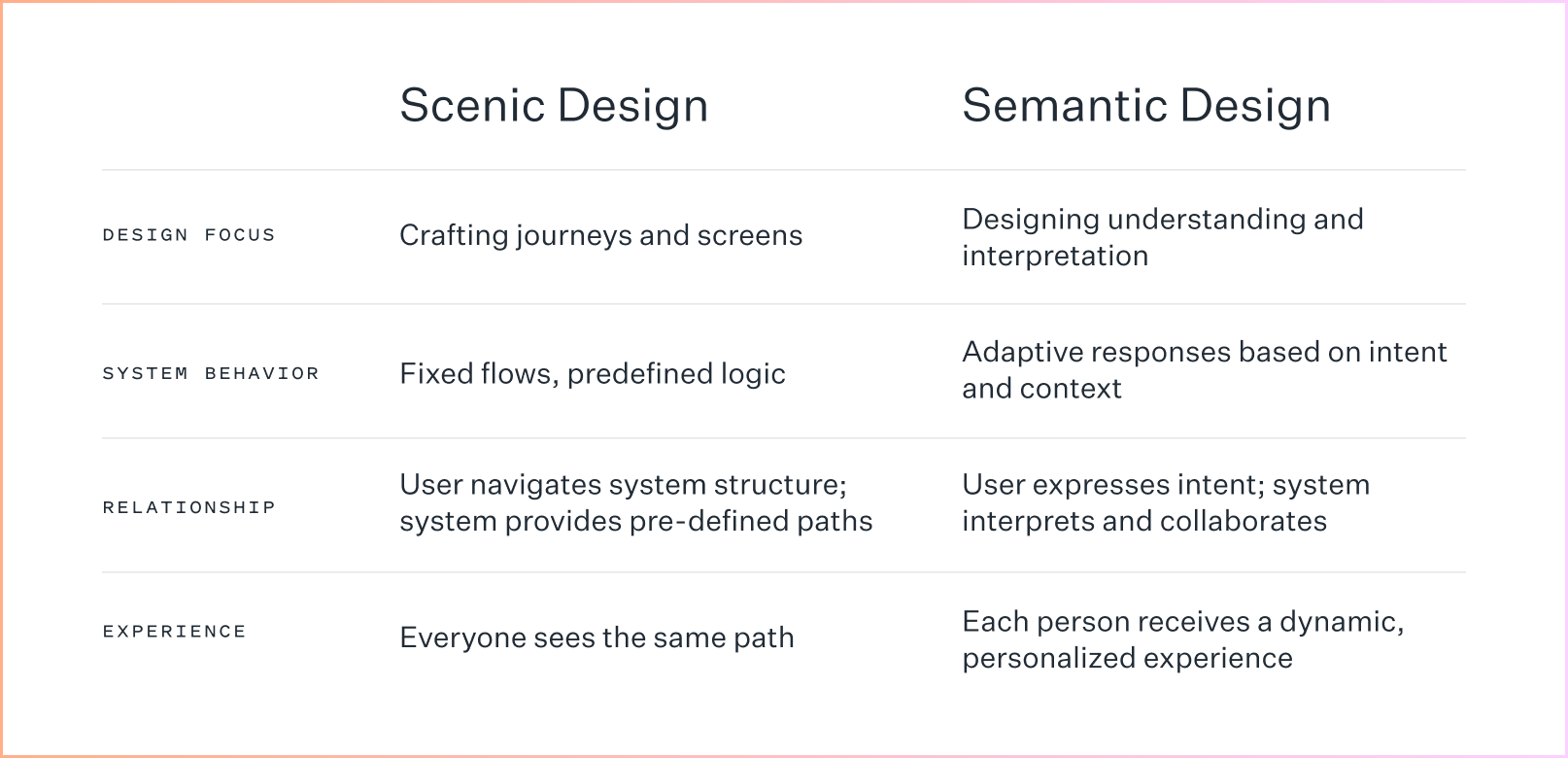

For decades, digital design was scenic, focused on a visual landscape of interfaces. We crafted beautiful buttons, perfected navigation hierarchies, and guided users through carefully choreographed journeys from screen to screen. The interface was the destination: load the right view, click the right control, follow the designed path.

But intent is semantic. It’s driven by meaning, purpose, and the unspoken why behind each action. As AI reshapes our relationship with technology, we’re shifting from scenic design (set paths and structured journeys) to semantic design (what systems understand).

The interface as destination

In the scenic paradigm, every digital experience followed a familiar script. Users navigated URLs, scanned menus, and translated their goals into the language of the interface. Click “Travel,” then “Flights,” then fill out departure, arrival, dates, and passengers. The burden was always on the user to map their intent onto the system’s structure.

This worked when interfaces were simple and tasks were predictable. But as workflows grew more complex, the scenic approach began to break down.

Consider Sarah, a product manager preparing for her team’s next release. She’s balancing deadlines with a lean team, trying to stay ahead of stakeholder feedback while keeping engineers unblocked.

In the scenic world, she opens her project management tool to create epics and user stories, checks her analytics for usage data, reviews mockups in her design tool, schedules stakeholder reviews in her calendar, pings engineers on Slack, and updates timelines on her roadmap. Each tool requires her to translate her goals into a different brand of interface logic.

From commands to context

We’re in a transitional moment where interfaces still offer explicit choices and manual controls, but beneath the surface, semantic understanding is beginning to emerge. Search engines understand natural language. Email clients draft replies. Design tools suggest layouts based on content.

Instead of asking, “What’s the best flow to accomplish this task?” we’re learning to ask, “How can the system understand and adapt to what people want to achieve?” But this transition is messy. We’re building systems that understand context, but still forcing users to interact through scenic metaphors.

Understanding over interface

Semantic design flips this relationship. In a semantic system, Sarah simply describes what she wants to accomplish: “We’re releasing the new collaboration feature next month. I need to coordinate final testing with engineering, get design sign-off, update stakeholders on timeline changes, and prep our rollout plan.”

The system understands her goals, surfaces relevant project status, drafts stakeholder updates, and coordinates a response across concerns. She’s no longer jumping between tools; she’s working with a system that understands what needs to happen and helps her get there. But this shift isn’t without complexity.

The challenge ahead

As semantic systems grow more capable, designers face a new set of challenges:

Agency

When systems infer intent, users risk becoming dependent on system reasoning rather than maintaining their own understanding. How do we preserve human agency while reducing cognitive load?

Transparency

Unlike traditional interfaces with visible controls, semantic systems make decisions behind the scenes. How do we design visibility into system reasoning and decision paths?

Context

These systems rely on rich context to interpret intent. How do we gather and apply that context thoughtfully, acting on environmental signals, personal history, and situational cues without sacrificing privacy or reinforcing bias?

Control

When systems interpret rather than execute, they can get it wrong. How do we preserve the ability to guide, override, or redirect, especially when the stakes are high?

Experience

Semantic systems risk erasing the moments that build brand and meaning. How do we preserve emotional engagement and experiential choice when systems optimize for speed and outcomes?

Alignment

As systems shape decisions and learn from behavior, they carry moral weight. How do we ensure systems align with human values, not just optimize for metrics?

Meeting these challenges will require new ways of thinking about user experience.

Designing for semantic interaction

The interface is no longer the frame. We’re shifting from designing screens to designing intelligence. That means shaping how systems engage with ambiguity, context, and the nuance of human goals.

Here are five principles for designing semantic systems:

Think in systems, not screens

Semantic design unfolds across touchpoints, platforms, and time. A single intent might surface in multiple contexts, across different devices. Design for when, how, and why intelligence appears.

Focus on relationships

Design for partnership, not just interaction. How does the system earn trust? How does it adapt to individual working styles? Use dialogue to explore how these relationships develop over time.

Design for ambiguity

Unlike interfaces with clear affordances, semantic systems must handle uncertainty, multiple interpretations, and evolving intent. Design guardrails that set boundaries for system behavior and clarify what’s fixed versus what’s negotiable.

Test for understanding

Traditional usability asks, “Can users complete this task?” Semantic testing asks, “Does the system understand what users want to accomplish?” Test for alignment, not just transactional success.

Preserve agency

Define when the system leads and when it defers. How does it balance taking initiative with waiting for direction? Design for what’s desirable, not just what’s possible.

Navigating the transition

Interfaces won’t disappear. They’ll become more ephemeral, adaptive, and aligned with intent. As systems grow more interpretive, the human side of design becomes more critical, not less.

Semantic design requires deep empathy for how people think, work, and make decisions. This means designing systems that explain their reasoning, invite correction, and maintain transparency, even as they handle complexity. The goal is to create systems that think with people, not for people.

This is a fundamental shift in how we approach digital design: from crafting beautiful, usable interfaces to building intelligent partnerships. For designers, it promises interfaces that don’t just look intuitive—they actually are.

Continue reading the full series on Human Computing

Part 2: Human Computing (The Manifesto)

Part 3: Beyond the interface (The Framework)

Let’s shape the future together. Subscribe to our newsletter and join the conversation on LinkedIn!

Doug Cook

Doug is the founder of thirteen23. When he’s not providing strategic creative leadership on our engagements, he can be found practicing the time-honored art of getting out of the way.